HISTORY OF THE TOMATO

Early Origins and Global Spread

The tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) originated in the Andean region of South America, primarily in modern-day Peru, Ecuador, and northern Chile. It was first domesticated by the indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica, including the Aztecs, who called it “tomatl.” When Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Americas in the early 16th century, they encountered the tomato and brought it back to Europe.

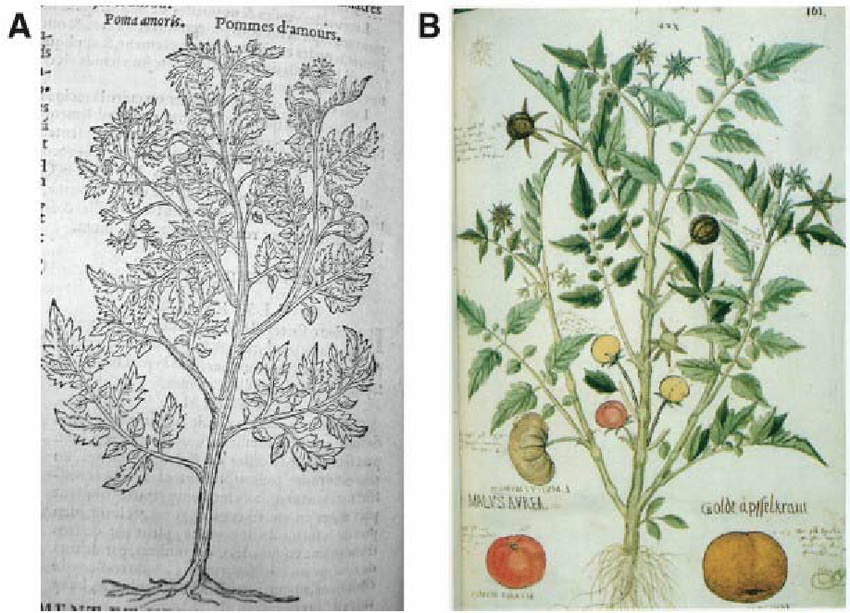

Arrival in Europe

The tomato was introduced to Spain around the 1540s. Initially, it was grown more for ornamental purposes rather than as a food crop. By the late 16th century, the tomato had spread to Italy, where it began to be incorporated into local cuisine. Its acceptance as an edible fruit varied across Europe, often being met with suspicion and considered poisonous due to its relation to the deadly nightshade plant (Atropa belladonna).

Introduction to the UK

The tomato’s journey to the UK likely occurred in the late 16th or early 17th century. The first known reference to the tomato in British literature appears in John Gerard’s “Herball,” published in 1597. Gerard, a prominent herbalist, described the tomato (which he called “Love Apple”) and noted its cultivation in Italy and Spain. However, he expressed doubt about its edibility, reflecting the cautious attitude toward the tomato at the time.

Initial Hesitation and Superstition

For many years, the British remained skeptical of tomatoes, primarily due to their association with the nightshade family. Tomatoes were often grown as decorative plants rather than food. It was commonly believed that tomatoes were poisonous, an idea perpetuated by their resemblance to certain toxic plants and the fact that they were sometimes served on pewter plates, which could cause lead poisoning when combined with the tomato’s acidity.

Gradual Acceptance

The 18th century saw a gradual shift in the perception of tomatoes in the UK. Increased contact with other European countries, particularly Italy, where tomatoes were widely used in cooking, began to change British attitudes. The tomato slowly gained acceptance as a culinary ingredient, albeit cautiously.

By the early 19th century, tomatoes were being grown more widely in the UK. The improvement of greenhouse technology allowed for better cultivation in the country’s cooler climate. Cookbooks from this period, such as Maria Eliza Rundell’s “A New System of Domestic Cookery” (1806), started to include recipes using tomatoes.

19th Century Boom

The Victorian era marked a turning point for the tomato in the UK. Advances in horticulture and transportation facilitated the widespread cultivation and distribution of tomatoes. Tomatoes became a staple in both home gardens and commercial agriculture. The development of new varieties suited to the British climate also contributed to their popularity.

During this time, the tomato’s culinary versatility became increasingly recognized. It was used in soups, sauces, and salads, becoming a key ingredient in British cuisine. The advent of canning technology further boosted the tomato’s popularity, allowing for year-round consumption.

20th Century to Present

The 20th century solidified the tomato’s place in British food culture. It became a fundamental component of many traditional dishes, such as the Full English Breakfast, which often includes grilled tomatoes. The rise of global cuisine and the influence of Italian, Mediterranean, and Middle Eastern cooking further integrated tomatoes into the British diet.

Today, tomatoes are one of the most popular and widely consumed vegetables (though botanically a fruit) in the UK. They are grown in a variety of environments, from large commercial farms to small allotments. The UK also imports a significant quantity of tomatoes, ensuring their availability throughout the year.

Conclusion

The history of the tomato in the UK is a story of gradual acceptance and eventual embrace. From its early days as a suspicious foreign plant to its current status as a beloved staple of British cuisine, the tomato’s journey reflects broader changes in agricultural practices, culinary tastes, and cultural exchange.